What if I told you that the catalyst for the industrial revolution and everything that followed was a screw? In the last installment of this series on mass production, we took a close look at the techniques used in ancient times to produce large quantities of products uniformly. In this installment, we’re going to look at how those innovations eventually led to the launch of the industrial revolution and I’m here to tell you, the jumping-off point was a screw. Yes, you read that right. A small bolt of metal with perfectly spiralled threads carved into its trunk. The assembly line that made your SUV possible, factories that pump out millions of the very same shoes you’re wearing right now, billions of cans of Cream of Mushroom soup, that piece of Trident you’re chewing on…. All of these things owe their existence to the almighty screw.

“But how?” You must be wondering? How does a tiny piece of metal lead to the culture of mass consumption we know and live in today?

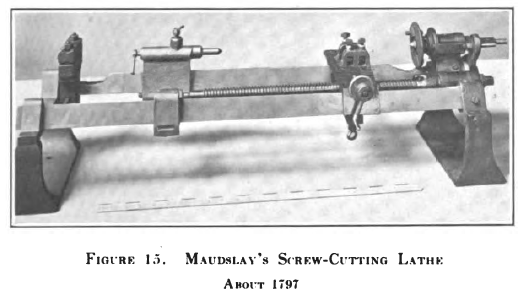

It all started in England with a man named Jesse Ramsden. Before Mr. Ramsden, who lived from 1735 - 1800, screws were made by hand with files, or with a hand-cranked lathe. While modern lathes had already been dreamed up by the likes of creative geniuses like Leonardo Da Vinci, a lathe with a slide rest, a guide screw and a change gear mechanism didn’t exist in reality until our buddy, Jesse decided to build one in 1775. This machine by Mr. Ramsden is the basis for all screw lathes in use today. Henry Maudslay followed suit with his own take on the screw-cutting lathe and tends to get most of the credit for creating them, but it was, in fact, Jesse Ramsden who built the first modern screw-cutting lathe that led the way down the path of uniformity to mass production. The mass manufacturing of little metal screws on a lathe brought large-scale, uniform production to industry.

Before Henry Maudslay built his own version of the screw-cutting lathe, he worked in the locksmith shop of Joseph Bramah. Together, the two of them perfected the hydraulic press in 1795. Otherwise known as the Bramah press, this bit of machinery enabled the shaping of metal with interchangeable consistency, speed and precision which opened the doors to the mass production of metal parts.

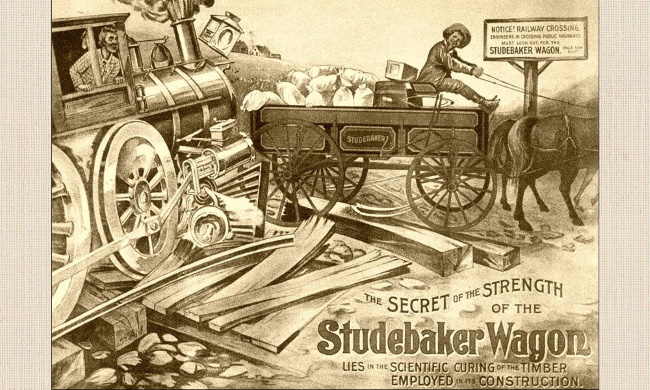

The screw-cutting lathe and the hydraulic press quickly gave way to the large scale production of many products, the most notable of which was the Studebaker wagon. Peter Studebaker was a resourceful, profit-minded man who bought up large swaths of land on which he built the beginnings of the Studebaker empire. These plots of land would require ore deposits, lumber sources and water flow to power his machinery. Peter built wagon-making factories that were designed to produce uniform wagons on a larger scale than ever before. When Peter died, his sons took over, implementing new hydraulic technology to increase the production numbers and introduce new products such as the Studebaker wheelbarrow. The brothers expanded into the West, following the gold rush, and opened up shop in California. Their wheelbarrow was in high demand as it solved many problems for those hoping to strike it rich with gold.

Things may have been rough for many parts of the United States of America during the Civil War, but for the Studebaker brothers, things couldn’t be any better. The Studebakers could barely keep up with the wagon orders they were getting from the US government. This demand led to new, faster production methods, inventions and factories. By the time Studebaker had transitioned from horse-drawn wagons to gas-powered automobiles, the name Studebaker was widely recognized as a leader of the industrial revolution.

Making use of the technology developed by Joseph Bramah, Henry Maudslay and Jesse Ramsden, the Studebaker empire pumped out 268,099 cars and 52,146 trucks.

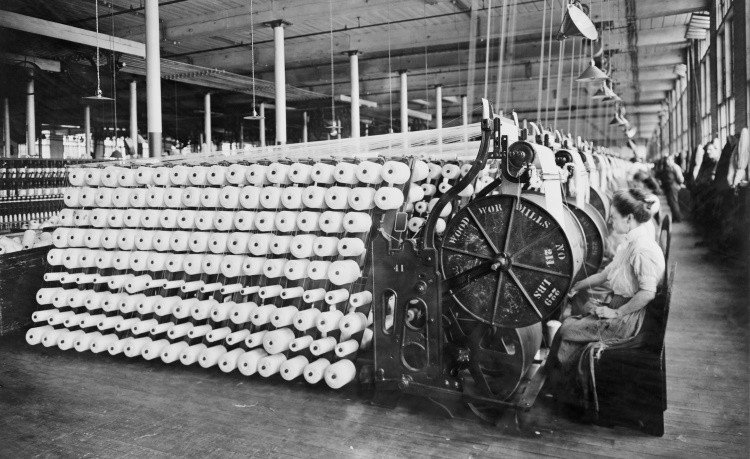

It wasn’t just metal-shaping technology that led the way to the Industrial revolution, however. Back in England, high demand for textile-based products forced the manufacturers to think up new ways to create these items uniformly and with greater speed. Prior to the 18th century, the textile business was operated by craftspeople who sewed, weaved and spun textiles by hand.

The flying shuttle was an invention that took a project previously requiring four skilled weavers and turned it into a one-person job. The textiles this machine could weave were also much larger which led to the ability to turn out more products, faster and with significantly less labor.

The flying shuttle’s high yield created another problem, though. Its use resulted in a much larger demand for thread and yarn. In fact, it created so much demand that it could not be met with the current yarn-producing methods at the time. Human ingenuity met that problem head-on when James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny which enabled one operator to spin multiple spindles at once. When previously one laborer was needed for each spindle, the spinning jenny enabled that same worker to operate 8 or more at once.

A few years later, Richard Arkwright patented a machine called the water frame that improved on the spinning jenny by adding water power. This sort of power produced a stronger yarn than the spinning jenny. On its first run, the water frame produced 128 threads at once.

Water power was then injected into the loom when the first automatic power loom was invented by Edmund Cartwright in 1785. This sped up weaving times exponentially and production of textiles had grown out of its need for artisans, skilled weavers and craftspeople. As with all automation, this led to upset and protest as unemployment peaked.

The introduction of steam power into factories had a profound impact on their output and displaced a lot of workers, as well. In the later years of the 1700s, the steam engine was adapted from a reciprocating mechanism to one that rotated, enabling its use in running machinery. Steam power had come a long way since inventor Thomas Savery’s creation of the one horsepower engine in the 1600s.

All of the innovations and technology that dragged global economies into the future led to a focus on efficiency, yields and production times. Factory owners wanted every ounce of work they could squeeze out of their employees and worked them to the bone. They found creative ways to obtain cheap labor such as the use of unmarried women and children in their workforces. The factories demanded 10-12 hour workdays and often workers would only get one day per week off.

Working conditions were even worse considering the rapid inclusion of new, heavy machinery that no one had experience with. Industrial accidents were normal. Dangerous fumes and extreme heat drew workers to exhaustion. These side effects of the Industrial Revolution are what led, eventually, to workers organizing and forming unions and in some cases, revolting against the factory owners.

The Industrial Revolution definitely had growing pains in its early days, but the human ingenuity and drive to innovate led us to this world where just about anything is accessible to most people. This is the hope that drove Henry Ford to implement his first automobile assembly line. Though Ransom Olds of Oldsmobile is credited with the patent for the automobile assembly line, it was Ford’s that had the biggest impact. Ford wanted to make his cars more affordable and therefore, more attainable by average, everyday people. He took the assembly time of one vehicle from 12 hours to just over two. This drastically reduced the price of the vehicle which enabled more people to purchase one.

The popularity of the assembly line grew like wildfire across the automobile industry and began to have an impact on other markets as well. Other factories and manufacturers looked at Ford’s example and realized they, too, could reduce the cost of production by a significant amount if they adapted the assembly line to their own needs. Once again, the way industry produced products changed across the board.

In our next installment in this series about mass production, we’ll take a look at how the assembly line took the world by storm and how our world adjusted to a new, faster pace of commerce. Check back in the coming weeks for that!